On the air with WUNC Radio

WUNC Radio’s Frank Stasio spoke with Malinda Maynor Lowery about the lessons we learn from those who came before us. It’s a discussion science fiction, scripture, and how Lumbee “outlaw” hero Henry Berry Lowrie would preserve kinship structures and right inequality during the current COVID-19 crisis. Listen to the April 22, 2020 The State of Things.

An essay by Malinda Maynor Lowery

Native American history contains some clues to grapple with our present crisis. We have a better understanding about why Native people died of infectious disease (surprisingly, it was more due to colonial policies than to lack of immunity), but also about why people survived. For Native people, and for many Americans hardest hit by this disease, that is the critical question right now. I am a member of the Lumbee tribe of North Carolina and a historian of race, identity, and sovereignty; through the experience of my ancestors, we can see clearly the relational lifeways that contribute to survival. Surviving coronavirus hinges upon our ability to adapt and re-form relationships, as history shows our ancestors did, rather than serve the systems that got us here in the first place.

Native American history contains some clues to grapple with our present crisis. We have a better understanding about why Native people died of infectious disease (surprisingly, it was more due to colonial policies than to lack of immunity), but also about why people survived. For Native people, and for many Americans hardest hit by this disease, that is the critical question right now. I am a member of the Lumbee tribe of North Carolina and a historian of race, identity, and sovereignty; through the experience of my ancestors, we can see clearly the relational lifeways that contribute to survival. Surviving coronavirus hinges upon our ability to adapt and re-form relationships, as history shows our ancestors did, rather than serve the systems that got us here in the first place.

What Would Henry Berry Lowrie Do in a Time of Coronavirus?

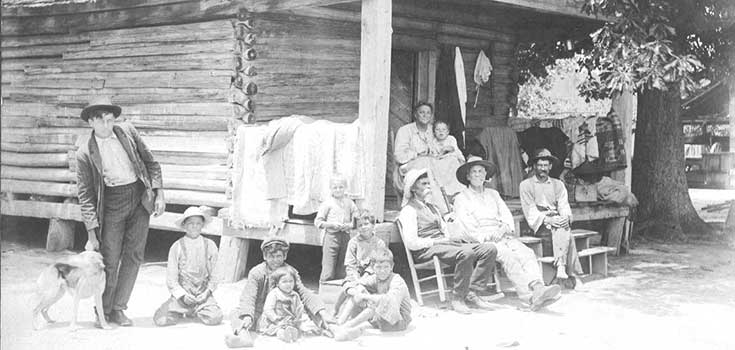

Lying awake late at night, trying not to worry if my husband has contracted COVID-19 at work today, I’ve begun thinking about my Lumbee Indian ancestors. The Lumbees are the largest tribe east of the Mississippi, over 55,000 enrolled members, with our homeland in southeastern North Carolina. It used to be remote, swampy land, hardly even registering on the maps of colonizers. But now I-95 runs right through it. Still, those speeding by often don’t know we’re there. Many Americans, of course, think American Indians are mostly dead and gone, of disease, if not warfare. The stories that we’ve heard about “virgin soil” diseases—millions of Indigenous people and African slaves dying of smallpox or other infections on this continent in continuous waves because we had no natural immunity—sound frighteningly familiar these days.

But a lack of immunity wasn’t why so many of my ancestors perished; they had seen disease before. As historian Paul Kelton and others have shown, Indigenous societies managed crisis intelligently, and protections for the vulnerable were woven into the social fabric. Healers could remove contagions through medicine and spiritual practice. They imposed successful quarantines. They managed food systems despite seasonal uncertainty, redistributing food and other goods in order to sustain communities. Hoarding was reviled. Young people learned that taking care of elders was a given. Back then, Europeans didn’t have vaccines or ventilators either; they too recognized that quarantine and basic medical care were the best ways to prevent the spread of novel viruses.

What brought on the first genocides of Native American people was European colonizers’ disruption of these carefully adapted societies. Kelton and others studying smallpox among Indigenous and African peoples have found that many more died than probably would have, if Native peoples were not simultaneously subject to violence and dispossession. They died because colonizers seized their arable land, enslaved them, waged war upon them, and diminished the political power my ancestors possessed to keep their people safe.

But our communities did survive, and so did the lifeways that prioritize relationships over systems. These waves of disease extended right up through the Civil War and the 1918 flu pandemic, but eventually the Lumbee birth rate began to far exceed the death rate. Our population grew, our community became stronger. While much of the discussion at this moment is about why people are dying, I lie in bed at night and think of why we have survived.

What was true then is true now: policy can prevent the spread of disease as much as social distancing and hand washing does. Then as now, once a disease is in a community, healers must be free to practice their knowledge and inform their communities. They must not be stopped by greed and politics. Colonization prevented our healers from doing their work and our people from accessing medical and spiritual care. Displacement and famine followed, and while we sit around hoping for things to go back to “normal,” many of our ancestors had no such chance to recover.

But we survived in part because of competent, local leadership, particularly from a man named Henry Berry Lowrie. Henry Berry was my great-great-great uncle; at the age of seventeen or eighteen, in 1863 or 1864, the Confederate army conscripted him, along with other Lumbee, Black, and white men, to build Fort Fisher in Wilmington, NC, the Confederacy’s most important port. The men had to move thousands of pounds of dirt every day, back-breaking work in unsafe living conditions where army authorities allowed yellow fever, dysentery, and malaria to infect the workers. Henry Berry, his brothers, cousins, and neighbors, suffered this treatment and survived to return home, where they mounted a rebellion against it, an eight-year campaign against the Confederacy and the forces of white supremacy that succeeded it in the South. He certainly lived in a time where he could not rely on the protection of his government.

What would Henry Berry do in a time of coronavirus? First, he would follow his mother’s and aunt’s orders to stay in the damn house, and wash his damn hands, out of respect for his elders. No spring break trips with his eighteen-year-old friends.

In his time, he robbed wealthy farmers and gave food to the poor. Today I think he’d take hand sanitizer, paper products, and PPE from retail corporations that have stockpiled it. Then he would give it to workers in health care and essential industries. He would compel the county sheriff to release prisoners and reduce overcrowding in jails, much as he did in 1871, threatening local officials with consequences if they did not release the wives and daughters they had imprisoned, hoping to bring his rebellion to heel. He would surely not stand for a senator’s profiting off the crisis. He might even enlist a cousin with the skills to hack into some offshore bank accounts and Venmo the money to local mutual aid associations. Above all, he would place the care for his community first.

As in Henry Berry’s time, our future survival is in relationships, in how we care for each other, and in what principles we use to do so. Disease will do its damage, but our survival depends on the resilience of the societies we have created. We will survive if our lifeways continue to establish buffers against fear.