#COVIDintheSouth

The Future and Truth Telling

UNC alumna Mikaela Morgane Adams, highlights Indigenous history to reveal connections between the South and the world. Dr. Adams, Assistant Professor of Native American History at the University of Mississippi and author of Who Belongs?: Race, Resources, and Tribal Citizenship in the Native South, provides examples from beyond the South to place Indigenous people at the center of global history, specifically the 1918 flu pandemic. Her work shows how the future lies in truth telling, shared understanding, empathy, and mutual respect. Adams’ essay helps us to see that while UNC’s home region is distinct in some ways, it is also inextricably connected to the world.

Social Distancing in the Age of Assimilation: The Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1920 in Indian Country

Mikaëla M. Adams

In recent weeks, we’ve all quickly had to learn how to practice “social distancing” in the face of the novel coronavirus now sweeping the globe. Social distancing, however, is not a new concept. Indeed, in the time before modern medicine it was the best—and often, only—way to stem the spread of infectious disease. This was certainly true during the influenza pandemic of 1918-1920, a deadly outbreak that devastated humanity a century ago and killed as many as 50-100 million people worldwide.[1] With no antivirals to lessen the severity of the virus and no antibiotics to combat secondary pneumonia infections, people’s best hope against the so-called “Spanish flu” was not to get sick in the first place. As many of us have discovered recently, however, social distancing isn’t always easy, especially if we haven’t yet experienced the full brunt of the outbreak. Social distancing requires sacrifice—we must give up things we hold dear for the future safety of ourselves and the community. It also requires trust—we must believe that the powers-at-be know what they are doing and have our best interests in mind when they issue their recommendations or orders. If we don’t trust the motivations of those making decisions, or if these directions seem unclear or contradictory, we are less willing to submit to the necessary sacrifices. As my research on the 1918-1920 influenza pandemic in Indian Country reveals, the same was true in the past. Native Americans, who had suffered more than a half-century of assaults on their way of life, were understandably suspicious when federal agents began prohibiting cultural practices—like funeral feasts, ceremonies, and dances—in the face of the flu. The cultural chauvinism of federal agents spurred indigenous resistance to social distancing protocols in the early weeks of the pandemic, which made this already at-risk population even more vulnerable to the ravages of influenza.

The influenza pandemic of 1918-1920 struck the United States at the height of the age of assimilation, a time period when the federal government devoted considerable energy and attention to the country’s so-called “Indian problem.” As the western Indian Wars drew to a close, reformers pressed for a new Indian policy that would “kill the Indian and save the man” by politically, economically, and cultural transforming tribal peoples into American citizens. This process included undermining tribal governments through extending federal jurisdiction over reservation lands, breaking up communally-held tribal territories into fee-simple allotments and selling so-called “surplus” land to white settlers, and reeducating indigenous children in rigid, military-style, English-only boarding schools. Officials also encouraged missionary work on reservations to rid Native people of their supposed “superstitions.”[2] To enforce its assimilationist agenda, the Indian Office sent a small army of federal agents into Indian Country to survey and supervise Native people. Assaulted on all fronts, tribal communities struggled to hold on to their identities and lifeways while also experiencing devastating economic losses. They were still reeling from these changes when a virulent new strain of influenza began its deadly global march.

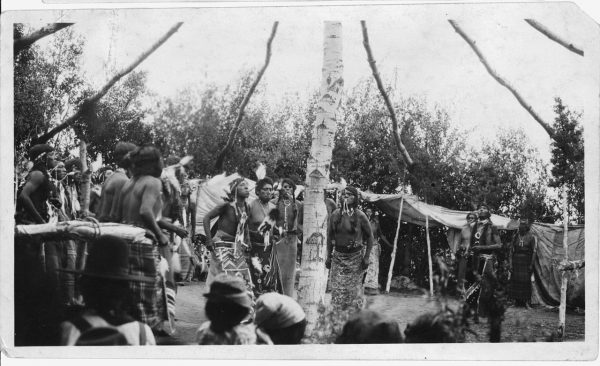

Installing quarantines, banning public gatherings, and limiting interpersonal contacts were some of the most effective medical tools available during the influenza outbreak. When federal agents endeavored to implement these social distancing protocols in Indian Country during the early weeks of the pandemic, however, they often did so with the ulterior motive of disrupting indigenous cultural practices. In South Dakota, for example, the superintendent of the Rosebud Agency banned funeral feasts for Sioux soldiers killed in the First World War, a global conflict that coincided with the pandemic. Although this ban had the solid medical goal of preventing large public gatherings that could spread disease, the superintendent couldn’t resist telling his indigenous charges that such feasts were “entirely out of harmony with modern progress” and thus inappropriate for people who otherwise were “standing so nobly by their Government in sending their sons to war.”[3] He ordered his agency farmers to make sure that the Sioux respected the ban. Similarly, in mid-October, 1918, the superintendent of the Cantonment Agency in Oklahoma complained that a ceremonial gathering of Arapahos on the reservation was nothing more than a cover for “gambling and other vices.” Rather that explain the medical danger of this assembly, he framed their gathering as a defiant regression to savagery and threatened to “call the sheriff if they did not break camp and go to their homes at once.”[4] A month later, the same superintendent disparaged a “gift dance” held by Cheyennes and visiting Ponca Indians. Once again the superintendent resorted to force to break up the gathering: he asked the county sheriff “to round up all visiting Indians and either send them home or if they refuse to go to put them in jail.”[5]

Native people viewed efforts to ban gatherings and cancel dances as a continuation of blatant attacks on their cultural identities and religious practices, and thus were often unwilling to accept these restrictions as medically necessary. This was especially true during the early weeks of the outbreak when they hadn’t yet experienced influenza first-hand and thus had only the word of their agents to rely on. Johnson Iron Bull, a Sioux from the Pine Ridge Agency in South Dakota, for example, wrote letters to white allies protesting that the government had “unjustly stopped” his people’s dances. He asked to have the restrictions lifted.[6] Similarly, Arapahos and Cheyennes in Oklahoma were “not inclined to cooperate with the authorities,” even under threat of arrest.[7] Northern Paiute and Western Shoshone people in Nevada were so used to assaults on their cultural practices that they remained unmoved even after their superintendent warned them of the danger of influenza. Instead of immediately disbanding from their assembled annual dance in mid-October, 1918, they insisted that they “be allowed to continue [to] dance two more nights.”[8] Decades of cultural attacks made Native people distrustful of federal motivations and wary of any effort to suppress their practices, which unfortunately increased their chances of exposure to influenza. Instead of fostering cross-cultural cooperation during the crisis, federal agents had created a hostile environment that bred misunderstanding and resistance.

Native suspicions of federal motivations become even more understandable when we consider Indian Office decisions regarding Indian boarding schools during the pandemic. Although local authorities across the country closed public schools during the worst of the outbreak to stem the spread of the virus—much like schools and universities have closed today due to COVID-19—the Indian Office decided that indigenous children had “as good a chance to escape the disease in a boarding school as they [had] in their reservation homes” and thus refused to close these residential schools. Federal officials justified this decision on the grounds that boarding schools had better medical facilities than reservations, which, they argued, meant that children had “a better chance for recovery at school than at home.” [9] Yet, financial incentives lay at the heart of this decision since Congress funded boarding schools on the basis of average annual attendance. The Indian Office knew that if it sent children home, it risked losing monetary support for its fundamental mission of assimilating indigenous children.

Native parents objected to the risk the Indian Office took by keeping their children in overcrowded schools during the outbreak. They knew that despite Indian Office assurances, many of these schools did not have the staff or facilities to care for dozens, if not hundreds, of sick children if disaster struck. Cheyenne River Sioux parents for example, wrote their superintendent to demand that he “discontinue the educational work on account of the Influenza.” If their children were forced back to school following the Christmas holidays, the Sioux protested, it would “cause the parents an extreme cold trip because we love our children as they are of our blood and must see them during their illness which will surely spread the Influenza.”[10] In another tragic case, parents from the Siletz Reservation in Oregon defied federal quarantine directives and visited their sick son at the Salem Indian School. Sadly, one of their younger children, who had traveled with them, contracted influenza upon arrival and died shortly thereafter.[11] Similarly, a pregnant mother desperate to see her influenza-stricken son at the Mount Pleasant Indian Industrial Boarding School in Michigan “developed flu, aborted, and died after about 30 hours.”[12] Despite parental protests and dangerous acts of resistance, the Indian Office refused to send boarding school students home to their families. In some cases, superintendents who were worried about school finances continued to enroll new students even after the disease had infiltrated their institutions.[13] For the Indian Office, the survival of their assimilationist program at times trumped the survival of actual Indian people, which further fostered feelings of distrust between Native people and the federal government.

The story of social distancing in Indian Country during the 1918-1920 pandemic highlights the importance of trustworthy leadership and consistent policies during moments of crisis. If we don’t have confidence in our leaders—if their recommendations seem politically- and economically-motivated rather than centered on protecting health—we are less likely to act quickly to implement social distancing measures. Messages become muddled and we don’t know where to turn for accurate information or appropriate instructions. The story also demonstrates the critical importance of cultural understanding and sensitivity during such times. It’s easy to dismiss people who don’t immediately follow medical recommendations as “backward,” “wrong,” or even “stupid,” but such attitudes don’t save lives. Only by meeting people where they are, respecting their histories and cultures, taking into account their prior experiences and concerns, and working together to find common understandings and solutions, can we hope to mitigate the ravages of deadly pandemics like the Spanish flu or COVID-19.

[1] For more on the influenza pandemic of 1918-1920 in the United States, see Alfred W. Crosby, America’s Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003); John M. Barry, The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History (New York: Penguin Books, 2004); Nancy K. Bristow, American Pandemic: The Lost Worlds of the 1918 Influenza Epidemic (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).[2] For more on federal Indian policy during the age of assimilation, see Frederick E. Hoxie, A Final Promise: The Campaign to Assimilate the Indians, 1880-1920 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984).

[3] Claude C. Covey to All Farmers, October 16, 1918, File: 92066, General Service, 732, General Service, Box 1505, Central Classified Files, 1907-39 (hereafter CCF, 1907-39), Record Group 75 (hereafter RG 75), National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. (hereafter NARA Washington).

[4] Robert E.L. Daniel to Cato Sells, October 14, 1918, File: 82027-18, General Service, Cantonment, Influenza, 732, General Service, Box 1501, CCF, 1907-39, RG 75, NARA Washington.

[5] Robert E.L. Daniel to Cato Sells, December 2, 1918, File: 82027-18, General Service, Cantonment, Influenza, 732, General Service, Box 1501, CCF, 1907-39, RG 75, NARA Washington.

[6] Eugene M. Camp to Cato Sells, March 10, 1919, File: 002133-008-0366, Series B, Indian Customs and Social Relations, CCF, 1907-39, RG 75, NARA Washington.

[7] Robert E.L. Daniel to Cato Sells, December 2, 1918, File: 82027-18, General Service, Cantonment, Influenza, 732, General Service, Box 1501, CCF, 1907-39, RG 75, NARA Washington.

[8] Francis A. Swayne to Indian Office, October 14, 1918, File: 96865-18, General Service, 732, General Service, Box 1506, CCF, 1907-39, RG 75, NARA Washington.

[9] E.B. Meritt to Reuben Perry, January 21, 1919, File: 84198-18, General Service, Albuquerque, Influenza, 732, General Service, Box 1502, CCF, 1907-39, RG 75, NARA Washington.

[10] Committee of Cheyenne River Sioux Indians in Cherry Creek District to James H. McGregor, December 18, 1918, File: 86625-18, General Service, 732, General Service, Box 1504, CCF, 1907-39, RG 75, NARA Washington.

[11] O.H. Lipps, Salem Indian School, to Cato Sells, October 31, 1918, File: 89463-18, General Service, 732, General Service, Box 1505, CCF, 1907-39, RG 75, NARA Washington.

[12] L.L. Culp to Cato Sells, March 3, 1920, File: 12638-20, Mt. Pleasant, 731, Mount Pleasant, Box 31, CCF, 1907-39, RG 75, NARA Washington.

[13] L.F. Michael to Cato Sells, November 28, 1918, File: 53689-1918, Pierre, 731, Pierre, Box 13, CCF, 1907-39, RG 75, NARA Washington.

Mikaëla M. Adams is Associate Professor of Native American history at the University of Mississippi. She received her Ph.D. in History from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2012. Her first book, Who Belongs? Race, Resources, and Tribal Citizenship in the Native South (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), explored themes of indigenous identity, citizenship, and sovereignty in the Jim Crow South. Her current book project examines the influenza pandemic of 1918-1920 in Indian Country. She also has published articles in the Florida Historical Quarterly, the South Carolina Historical Magazine, and the American Indian Quarterly.

Mikaëla M. Adams is Associate Professor of Native American history at the University of Mississippi. She received her Ph.D. in History from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2012. Her first book, Who Belongs? Race, Resources, and Tribal Citizenship in the Native South (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), explored themes of indigenous identity, citizenship, and sovereignty in the Jim Crow South. Her current book project examines the influenza pandemic of 1918-1920 in Indian Country. She also has published articles in the Florida Historical Quarterly, the South Carolina Historical Magazine, and the American Indian Quarterly.